Free will, literally, is the power or ability to control and regulate one’s actions and decisions.

You probably believe in the existence of free will and think that all your actions so far have been chosen and carried out by your own will.

However, the experiment I’m about to discuss might make you question the existence of free will as you have believed until now.

In 1965, German neuroscientists Hans Kornhuber and Lüder Deecke published a paper that introduced a new concept.

This concept, called the “readiness potential,” refers to the electrical changes in the brain that occur one second before actually performing an action.

Using this concept, Benjamin Libet conducted an experiment in 1979 to determine the existence of free will.

Before Libet’s experiment, there was no method to measure the exact moment a subject made a conscious decision, so Libet had to devise a new approach.

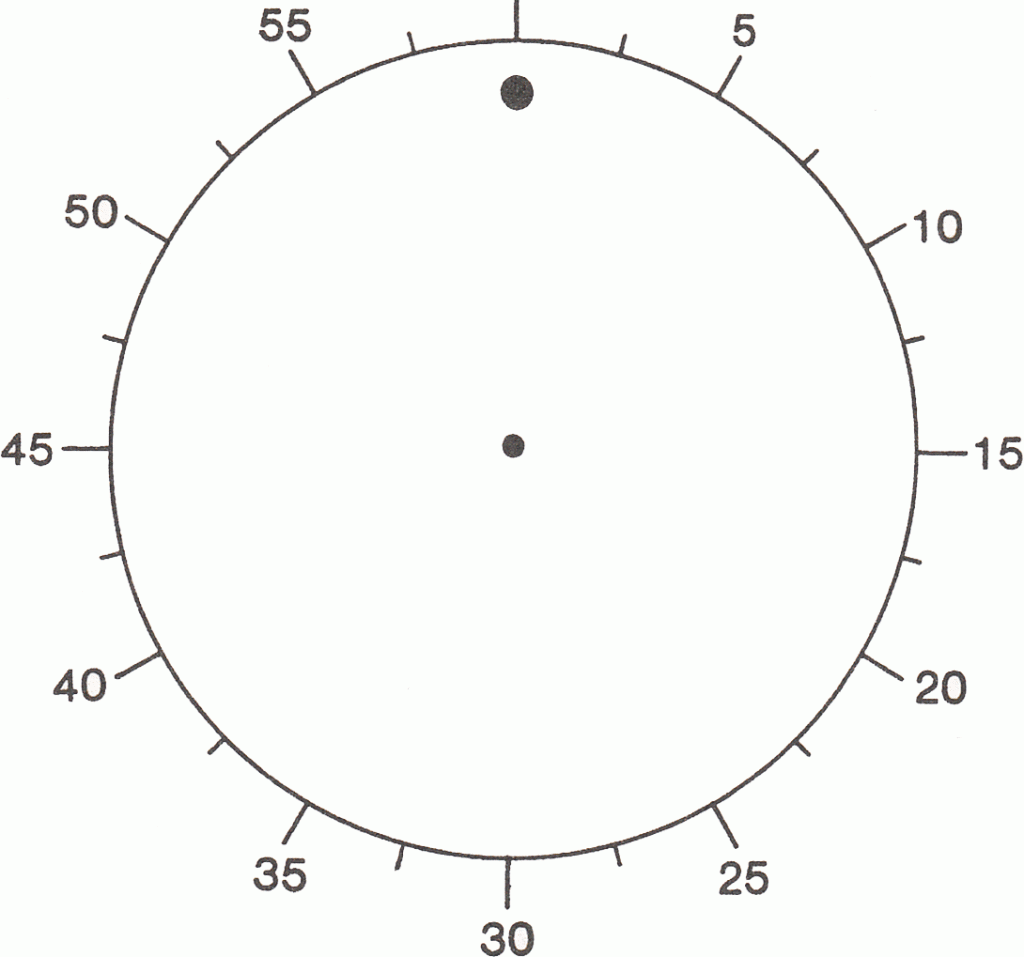

Libet decided to use a clock.

If the subject could report the exact time they decided to move their hand while looking at a clock, they could inform the experimenter of that time.

Scientific measurements need to be very precise, and this method relied solely on the subject’s subjective feeling, making it highly intuitive.

However, since there was no other method, Libet proceeded with the experiment using this approach.

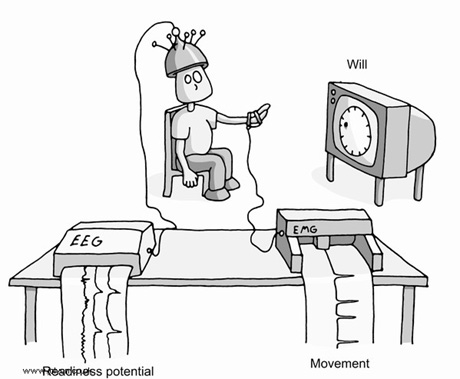

Libet attached electrodes to the subjects’ heads and their right wrists, and asked them to focus on a monitor 1.8 meters in front of them.

As shown in the diagram, the dot on the monitor made one full rotation every 2.56 seconds.

The subjects were instructed to move their right wrist at the moment they chose.

Through this experiment, Libet was able to measure the actual time of movement using the electrodes attached to the wrist and the time of the readiness potential using the electrodes attached to the head. He also measured the moment the subject decided to move their finger by noting the position of the dot on the clock.

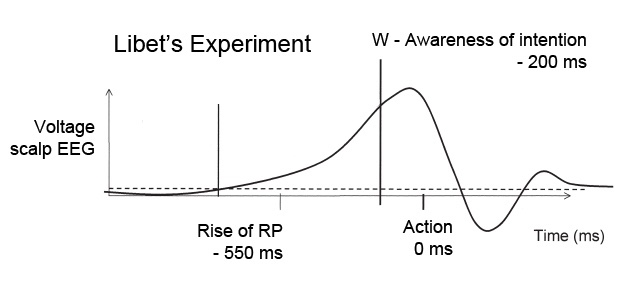

The above diagram simplifies the experiment into a graph. According to the graph, the subject decided to move their finger 0.2 seconds before the action, but the readiness potential was activated 0.55 seconds before the action.

This graph shows the result of one subject, but other results showed a similar pattern. While the exact timing varied, the readiness potential was always activated before the subject consciously decided to move their finger.

The conclusion of the experiment was clear:

“Humans do not have free will.”

However, Libet was not satisfied with this result.

He proposed a new theory to counter this conclusion, suggesting that conscious decisions could be overridden by what he called a “veto decision.” Through new experiments, he demonstrated that 0.2 seconds were enough to cancel a planned action, concluding that while we do not have free will, we have “free won’t”—the ability to not act on impulses.

However, since the readiness potential was also activated during the veto decision, this conclusion was deemed meaningless and discarded.

As you might have expected, this experiment sparked a lot of controversy. The idea that we don’t have free will is unsettling to many. Some people rejected the results, arguing that the brain signals occurring milliseconds before a decision are merely preparatory signals.

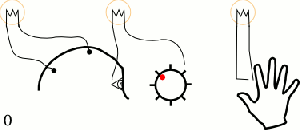

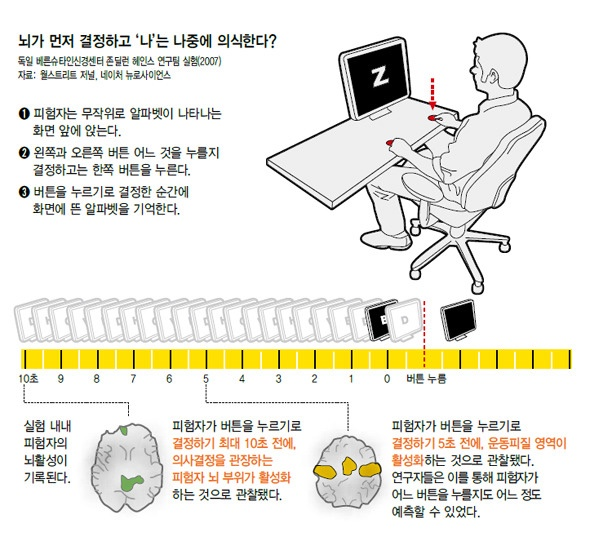

However, in 2007, a more sophisticated experiment conducted by neuroscientist John-Dylan Haynes and his team found that our brains make decisions up to a staggering 10 seconds before we are consciously aware of them.

Not just 0.2 or 0.5 seconds, but up to 10 seconds. Even considering the brain’s electrical signals and their speed, this is not a slow response. The brain was making decisions a full 10 seconds before the subject became aware of them, leaving little room for rebuttal.

The diagram above outlines Dr. Haynes’ experiment. The experimenter could even predict which button the subject would press.

As the description of the diagram indicates, this experiment also clearly demonstrates that humans do not have free will.

People who didn’t fully understand this experiment might say, “Since the brain is part of my own body, the brain’s choice is the same as my choice, so we do have free will.”

This statement is incorrect because the self, the part of us that we recognize as our identity, cannot perceive the brain’s choices or influence them in any way. In other words, the very notion of the self, which we consider as ‘us,’ is an illusion that does not truly exist.

We believed that we lived our lives seeing what we wanted to see, eating what we wanted to eat, and doing what we wanted to do.

But all of that was a lie.

Is there a soul? It’s doubtful. If our self-awareness is an illusion produced by brain activity, then without the body, there is no self to be perceived. Even if we were to generously concede the existence of a soul and call it the body’s energy, what good would it do? It’s just energy. It’s simpler and more logical to say there is no soul, making it easier to explain the world we live in.

Let’s assume there is an artificial intelligence that acts perfectly like a human through machine learning.

AI does not have a self-awareness; it merely selects appropriate learned behaviors for given situations.

However, unless we examine its circuits, to us, it appears that the AI is making appropriate decisions for the appropriate situations.

Similarly, even though we do not make direct choices in our lives, we have the illusion of self, which leads us to believe that we are making choices.

So, if we say that humans have self-awareness, shouldn’t we also say that AI, perfected through machine learning, has self-awareness?

If so, should AI also be granted human rights and be respected?

Even though AI is not a living being, if it has self-awareness and experiences mental suffering, wouldn’t it be morally wrong to ignore all of that as intelligent beings?

Perhaps all of this is a needless concern.

Since we’re dealing with something that doesn’t exist, we can simply assign meaning to it as we see fit.

Failing to assign meaning to the realm of self-awareness creates a significant contradiction in our society’s punishment of crimes.

Their self-awareness does not exist, and they did not commit crimes out of free will. Moreover, the suffering of the victims is also an illusion since their self-awareness is an illusion. Therefore, we cannot completely ignore the concept of self-awareness.

However, the fact that we do not have free will remains unchanged, and how should we as individuals accept this?

Who knows? Even writing this text is not out of my free will. However, I don’t think we need to become too despondent or give up because of this fact.

The free will we thought we had wasn’t taken away by this experiment; we never had it to begin with, and we’ve lived just fine without it. So, I think we can continue living as we always have.

In fact, accepting this reality might even expand the concept of “intellectual activity.” Instead of only considering “intellectual beings” as subjects of interaction, we could also consider AI—traditionally seen as mere tools—as our companions in humanity, potentially helping us design a better future.